San Francisco Chronicle; December 1, 1997

S.F.

Scientists Trying to Pick Right Lizards -

Repopulation plan will bring species to Galapagos Isle

By David Perlman

Chronicle Science Editor

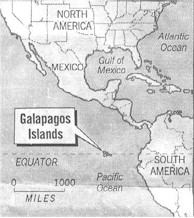

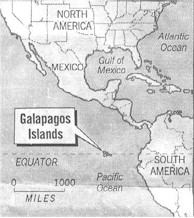

Pickled in alcohol for more than 90 years, 26 rare iguanas from the Galapagos Islands may solve a vexing genetic mix-up and resettle a unique breed of the lizards in their ancestral home. This is no "Jurassic Park" fantasy, but a major scientific effort to track and preserve the lineage of some of the strangest creatures on Earth.

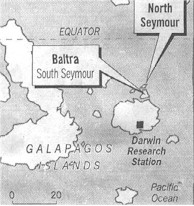

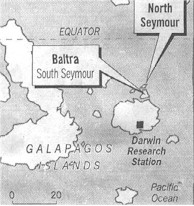

A team of scientists at the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park is hoping that DNA extracted from the long-dead iguanas will help them find the right variety to populate an island where World War II drove local lizards to extinction. The old iguanas have been quietly soaking in their alcohol baths at the Academy ever since they were collected from a cactus-studded island, now called Baltra, during the institution's first Galapagos expedition in 1906. Researchers from the University of New Mexico have been working at the Academy to extract tissue samples from the preserved iguana specimens and hope that genetic analysis will help them match the creatures with one of two populations that now live on an island only eight miles away.

During the 1930s, scientists apparently mixed up two distinct genetic varieties of the lizards when they moved some from an island then known as South Seymour to nearby North Seymour. South Seymour is now called Baltra; it is the site of the principal Galapagos airport, where tens of thousands of tourists arrive each year to cruise the islands and view their unique wildlife. The archipelago's finches, tortoises, lizards and plants first inspired Charles Darwin to reflect on the varieties of species there and later led him to his revolutionary theory of natural selection as the key to evolution. Among the weirdest of Galapagos animals are the three distinct species of land iguanas, whose wrinkled yellow bodies, dragon-like spiny crests and long tails vary strikingly among the eight islands where they are now known to live.

The airport on Baltra - named South Seymour by early English sea captains - was built at the beginning of World War II as an American air base to defend the Panama Canal. By the end of the war, after all the construction and bustling troop activity, the iguanas there were all extinct. But well before the war, other expeditions had collected iguanas from Baltra and moved them to nearby North Seymour island, where no iguanas had apparently ever lived. The immigrants promptly began nesting, breeding and rearing their young. But somewhere along the years that followed - and no one knows why or how - a few other alien iguanas were introduced into North Seymour, and that tiny island only eight miles from Baltra became home to two genetically different iguana populations.

For centuries throughout the Galapagos Islands, wild pigs have been digging up iguana nests to eat the eggs. Wild cats have hunted the young ones. Wild dogs have killed the adults, and wild goats have wiped out vegetation that the lizards need to live. But for more than 20 years, the Darwin Research Station and the Ecuadoran government's Galapagos National Park Service have run an active program to rescue the endangered iguanas. The effort includes a captive breeding and rearing program for each genetic variation to repopulate its native island. Active leaders in that iguana conservation project have been the University of New Mexico's Howard Snell, a herpetologist, and his wife, Heidi Snell, who have worked in the Galapagos aboard their boat the Prima since 1980. Since then, they and Galapagos Park Service conservation workers have helped move nearly 100 iguanas from North Seymour to protected breeding grounds at the Darwin Station, and 50 of their offspring have been released to thrive anew on Baltra.

But a mystery remains: Are the lizards now on Baltra really descendants of the original ones that once lived there, or are they some other genetic variant that somehow got mixed in when their ancestors lived on North Seymour? For all scientists and conservationists concerned about evolution, it is crucial to make certain that the iguanas on Baltra are in fact the same genetic variants that existed there nearly 100 years ago - and that probably existed when Darwin saw his first Galapagos iguanas from his ship the Beagle in 1835.

So Heidi Snell and Jennifer Brown, a gene sequencing graduate student in biology at the university in Albuquerque, came to San Francisco recently to study the pickled iguanas at the Academy of Sciences and prepare to figure out which living lizard group on North Seymour island the old specimens from Baltra matched. Snell painstakingly counted the hundreds of rows of scales on the heads of the 26 iguanas because the scales on each population group vary from island to island. And Brown, with rubber gloves wielding surgical knives and forceps, extracted dozens of tiny tissue samples from the animals' bodies and brains. The DNA that Brown hopes to retrieve is an extremely fragile molecule, and most preservatives like formalin destroy it. Alcohol, however, may not damage DNA at all, Brown says. As Brown extracted her tissue samples amid the aroma of ethanol rising from the iguana bodies, she explained why the work is so important:

"All over the world," she said, "conservation biologists are becoming more and more concerned about the loss of biodiversity, because species after species of plants and animals are disappearing. And when you talk about island populations, you're talking about the most endangered species of all. So since the animals of the Galapagos - like the land iguanas - exist nowhere else on Earth, once they vanish there's no way to restore them. If we can really make certain just which iguanas belong on Baltra and move more of the same kind there, we'll know we have restored an extinct and unique population on the island for the first time."