Their report, being published today in the journal

Nature, has amazed scientists, who have been arguing since early

this century about whether such journeys were even remotely

possible, let alone observable.

Their report, being published today in the journal

Nature, has amazed scientists, who have been arguing since early

this century about whether such journeys were even remotely

possible, let alone observable.The New York Times; Thursday, October 8, 1998

Hapless Iguanas Float Away And Make Biological History

By Carol Kaesuk Yoon

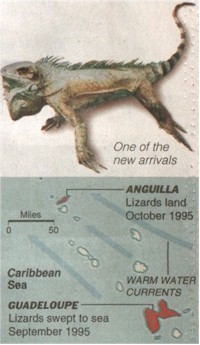

Fifteen iguanas on a tangle of waterlogged trees, tossed into the Caribbean Sea by a hurricane, apparently floated 200 miles from Guadeloupe to Anguilla and into biological history, scientists say.

Their report, being published today in the journal

Nature, has amazed scientists, who have been arguing since early

this century about whether such journeys were even remotely

possible, let alone observable.

Their report, being published today in the journal

Nature, has amazed scientists, who have been arguing since early

this century about whether such journeys were even remotely

possible, let alone observable.

By documenting the 1995 voyage of the 15 iguanas -- enough to form a new population -- the report provides the first clear-cut evidence in support of biologists who argue that seemingly impossible journeys like this could have been an important avenue for the dispersal of species around the world.

"It was a major invasion," said Dr. Ellen J. Censky, a reptile expert who has worked on Anguilla and was the lead author of the paper.

"I got a phone call saying iguanas had come onto the island," said Dr. Censky, now director of the Connecticut State Museum of Natural History at the University of Connecticut. "My first thought was that that couldn't have happened. Then somebody sent a snapshot. I thought, 'My God, that's it, that's it.'"

Dr. James H. Brown, an ecologist and biogeographer at the University of New Mexico, said: "It's a spectacular observation. Some of the things nature can do are pretty incredible."

The journey of the iguanas, land-loving animals, began in September 1995 when two powerful hurricanes moved through the eastern Caribbean. A month later the iguanas, fearsome-looking creatures up to four feet long that resemble dinosaurs, washed up on Anguilia's shores on an immense raft of trees, the Nature paper reported.

Dr. Censky said the lizards, which rest in trees, were probably blown down with them into the sea. She and her colleagues studied the tracks of the two hurricanes, Luis and Marilyn, and ocean currents and decided that the lizards probably came from Guadeloupe.

"I was completely surprised to see iguanas coming," Cleve Webster, a fisherman on Anguilla, said in a telephone interview.

Mr. Webster, who witnessed the invasion with his brother while they were checking lobster traps, said, "One iguana, he was on a log and the length of his tail was hanging over into the water."

Dr. Censky, along with Dr. Judy Dudley, a United Nations volunteer in Anguilla, and Karim Hodge, an employee with the Anguilla National Trust, interviewed witnesses to the iguana landing and then tracked and monitored the iguanas as they dispersed. Dr. Censky said her team was able to verify 15 animals, but suspected there were more. Identifying the lizards, known as green iguanas, as outsiders was simple, researchers said. They have a blue-green coloration and dark rings around their tails, making them easily distinguishable from the other iguana species on Anguill, which is brown and has a plain tail.

Though the arriving iguanas appear to have been weak, dehydrated and, in some cases, injured, some survived. In March, researchers said they found what appeared to be a pregnant female iguana, the last element of a successful colonization of a new species, which made the observation of the rafting significant. Because the animals appear to be reproducing, the researchers said they believed the new arrivals had established themselves, though other scientists said it was still too soon to tell.

While some Anguillans are concerned about the possible ecological impact of the new lizards on the island, Dr. Censky said she was not because their arrival and any changes brought by them would be entirely natural.

The new study bolsters the claims of those, like Dr. Blair Hedges, an evolutionary biologist at Pennsylvania State University, who have been advocating this type of rafting as a major explanation for the distribution of animals on islands in the Caribbean and elsewhere. Isolated ocean islands like the Hawaiian Islands would be devoid of terrestrial animals were it not for rafting, or the transportation of species by people.

"In my mind, it's not unexpected," Dr. Hedges said. "If we can see green iguanas land on Anguilla in 1998, just think of all the storms in all the millions of years and there is a real probability of getting anywhere in the world."

Other researchers, like Dr. Ross MacPhee, curator of mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History, while acknowledging that rafting clearly could occur, were not sold on its wholesale importance. Dr. MacPhee said he still thought ancient land bridges, stretches of land long since disappeared that are hypothesized to have connected islands in the Caribbean to South America, were likely to be a much more important mechanism for getting animals to islands.

Dr. MacPhee said land bridges were particularly important for mammals that did not tolerate starvation or dehydration as well as reptiles.

"We don't have to have to infer little drowned rats hanging desperately on to tree trunks," he said, "to explain why the faunas look the way they do."

In fact, rafting is just one of a number of seemingly outlandish mechanisms, which researchers have had to infer to explain how different creatures have arrived where they are today. Among the harder-to-believe explanations have been geologically implausible land bridges or the suggestion that fish might have been swept up in tornadoes and moved across land to establish themselves in other bodies of water.

Rafting, for some, was equally hard to believe until now. While there have been many records of single, usually small, animals drifting about the ocean, it takes two to set up a new population (unless one is a pregnant female).

Dr. Censky said, however, that the only previous evidence that multiple animals might have rafted together was a 30-year-old paper documenting three toads found floating on a log in the middle of a lake. " It wasn't even over-the-sea rafting," she said.

But in biogeography, a field that by its very nature seems to invite wild speculation, the seemingly wild explanations are often confirmed, as in the report today. Years ago the suggestion that some species are where they are because the continents themselves moved was met with the most intense ridicule. Today it is dogma, leaving the theory's early proponents with the last laugh.

"Over the long term," said Dr. Brown of the University of New Mexico, "improbable events become highly likely. Not everything is going to get everywhere, but things will definitely end up in surprising places."